Collated Responses from the Higher Education Institutions of the Catholic Church regarding Replacement of UGC with HECI

24

th Jul, 2018

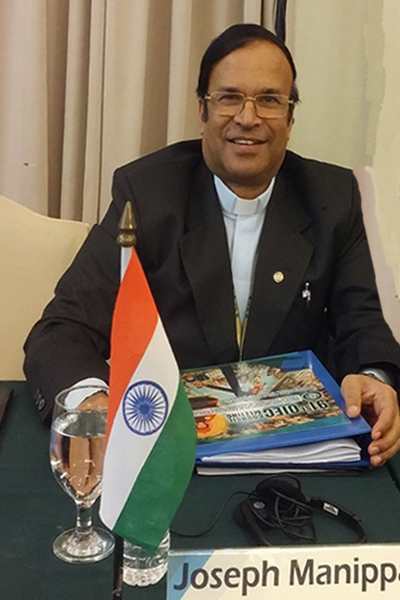

FR. JOSEPH MANIPADAM, SDB, THE SECRETARY OF THE CBCI OFFICE FOR EDUCATION AND CULTURE

17th July 2018

To,

Shri Prakash Javadekar,

The Honourable Minister of Human Resource Development (GoI),

302-c ShastriBhavan,

New Delhi.

Sub: Compiled Responses regarding HECI Act 2018 from the Catholic Church

Dear Sir,

Greetings from the CBCI Office for education and Culture, New Delhi! Several of our Higher Education Institutions and Associations of Higher education have responded regarding the above subject, on or before 7th July to reformofugc@gmail.com. However considering the importance of the matter under consideration and the relevance and seriousness of the suggestions forwarded, I am sending a collated response again to you for your valued consideration and necessary action before the draft is passed in a hurry and before it is taken up in the Parliament for discussion.

Thanking you

Yours Sincerely,

Fr. Joseph Manipadam SDB,

National Secretary, CBCI Office for Education and Culture, New Delhi

Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of University Grants Commission Act) Act 2018

Recommendations to MHRD – from the Region of Goa:

At the outset, we place before you a concern pertaining to the time allotted, by the MHRD for a comprehensive analysis of the bill, by the general public and institutions of higher learning, have been quite short. The MHRD made public the proposed the HECI Bill on 27th June, 2018 and set the deadline for 7th July, 2018 to send in the responses. A mere 11 days for discussion, is too short a time to posit any serious and formidable critique to the bill, from various stakeholders such as Teachers, Students and parents, who ultimately would be affected by this legislation. Given that education has its ramifications on the nation and society as a whole; it is of utmost importance, that the MHRD recognize the magnitude of this bill. In the interest of all the stakeholders, and the nation, we request you to extend the deadline for submission of comments and suggestions to a later date.

Having stated this, let us take this opportunity to state on record, that the intention with which the MHRD has introduced the Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of UGC) Bill, 2018 wherein you have identified the issues of quality in higher educational institutions of India; which is also affirmed through the QS World University Ranking wherein Indian universities have failed to make a mark, time and again, which is an indicator towards the ills that are confronting universities in our country; is shared by us as well. However, the panacea provided by the MHRD to correct the anomalies of the education through the proposed HECI Bill, 2018 is premature and fraught with problems. We would like to present our arguments, to qualify our statement.

The points presented below reflect our trepidations over the Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of UGC) Bill, 2018:

1) The Bill is ambiguous on several counts. It fails to provide a clear cut section on “definitions” that clarify what the legislation means by “quality”; “less government and more governance”; “affordability” etc.

2) The proposal to dissolve the UGC is premature and replacing it with the HECI provides room for distortions and arbitrariness in promotion of quality education. The UGC as a premier body is a body of intellectuals meant for intellectuals that has been functioning for over 60 years now. Instead of replacing the UGC with HECI, we strongly recommend strengthening the structural and procedural aspects of the UGC.

3) The Bill also introduces the dichotomy between the “quality” control, managed by the HECI; and the grant control, solely the prerogative of the MHRD. The UGC presently performs both these functions, and it has done it with considerable success. We propose that the UGC should continue performing both these functions. Given the role assigned to the HECI and the MHRD, in the HECI Bill, the intention of centralizing the system of funding is clear.

4) The Bill has not been deliberated with stakeholders at the state level. Education as a subject is within the domain of the Concurrent List. Therefore, the Centre and the State have an important say in matters pertaining to education. However, a careful analysis of the bill clearly point towards the exclusion of states in matters of higher education. The bill provides room for the centre to be the sole authority in matters of education.

5) The entire process of quality assessment performed by HECI and the pattern of funding could be fraught with friction and also arbitrariness exercised in extension of grants to institutions.

6) The bill also introduces a system which rules out the face to face interaction between the higher education institution and the funding body.

7) Why the legislative autonomy is centralized it should be more consultative, deliberative and democratic?

Concerns:

8) Ref: Section 3.6: While the UGC Act 1956 clearly mandated that the Chairman of the Commission “shall be chosen from among persons who are not officers of the Government or any State Government” – precisely with a purpose to maintaining the autonomy of the Commission from any form of direct interference by governments – Section 3.6 of the Draft HECI Bill drops this necessary condition for the Chairperson’s appointment. The Chairperson of the proposed Higher Education Commission can now be selected from among functionaries of the Central or State governments, provided he/she satisfies either of two conditions listed under Section 3.6 – none of which comes into conflict with his/her holding an office of the government at the time of appointment.

Not only that, the same Section 3.6 makes the appointment of the Chairperson of HECI incumbent on the decision of a Search-Cum-Selection-Committee (ScSc), headed by Cabinet Secretary and flanked by the Secretary of Higher Education (both GoI employees). The principle of non-intervention that was enshrined in the letter of the UGC Act, as an acknowledgment of the need for autonomy in educational policy-making, is discarded by the proposed HECI Bill with regard to the very setting up of the Commission.

9) Ref: Section 23: The element of criminality and culpability mentioned in the bill is un-constitutional and against natural justice, especially in the context of a proposed educational bill.

10) Ref: Section 15(4) (l): The HECI is empowered to “specify norms and processes for fixing of fee” and to advise governments on “steps to be taken to make education affordable for all”. While the UGC Act had a very detailed section on fees (as well as subsequent regulations) and a prohibition on donations, the HECI Bill makes this singularly and is the most important provision mere matters of advice. This also signals the move from a state subsidy model to a loan-assistance policy for select private individuals – thus making way for a general user-pay principle in the funding of public education.

11) Ref: Section 24: As per the Sections 12(e)-(g) of UGC Act 1956 prescribes an advisory role for the Commission, with regard to information necessary or sought by the Central or State Governments. The Draft HECI Bill 2018 performs a complete inversion of this. It mandates the setting up of an Advisory Council within the Commission, chaired by the “Union Minister for Human Resources Development” and with “Chairpersons/Vice-Chairpersons of all State Councils for Higher Education as members”. The presence of a government-controlled advisory organ in the Commission, headed by the HRD Minister, puts all pretensions of legislative autonomy to rest and structurally subordinates higher education to the political intentions of the government of the day.

12)Ref: Section 3(6) (b): We find it objectionablethat the Draft Bill maintains that the Chairperson of the proposed Higher Education Commission of India may be “an Overseas citizen of India”. We find this unacceptable, as the Chairperson of such a Commission must be someone who is a resident citizen of India, bound by its Constitution, with the requisite experience of teaching/administration in the Indian Higher Education sector.

13)Ref: Section 3(8): Teacher representation is minimal for HECI. The quantum of representation in UGC of teachers is optimal. Reform the UGC and deal with the problem rather than introducing the HECI. Eminent scholars and National Fellows should have a greater representation in the UGC.

14)Ref: Section 15(3) (a): The existing reservation system for the SC/ST/OBC and the linking of quality aspect to the higher educational institution suffer from structural defects. The system would not be geared to take into account the deprivation factor that the community has been confronted with. The HECI Bill does not provide a “weighted formulae” to uniformly assess the issue of quality across social classes. This would be detrimental to the reserved community with reference to learning outcomes specified in 15(3) (a).

15)Ref: Section 15(3) (b): We should follow the UGC prescribed minimum standard for teaching and research as institutions for higher education focusses on epistemic freedoms. Maximality is a relative concept.

………………….

The New Educational Bill abolishing the UGC is detrimental to Higher Education in India: (from His Eminence George Cardinal Alencherry; Kerala Region)

The new Educational Reform as announced by the Minister of HRD on June 28,18 has far –reaching negative consequences for the development of higher Education in India and will be very detrimental to the progress of collegiate and University education in the country.The improvement that is envisaged by the Bill is very minimal in importance in the sense the new Council that is planned to be formed has only limited powers. The new Council is given the power to punish errant institutions and impose fines for violations. But the disbursal of grants is reserved to the HRD Ministry of the Government. The ministry will have more control and it will try to coerce educational institutions to follow the political ideology of the party that controls the Central government.Not only that, the colleges and Universities will have to approach the Ministry for even minor matters. The Ministry also gets the power to withdraw the approval granted to colleges and Universities.

In the existing set-up, the UGC is an independent body; the Chairman and the members of the body after their appointment cannot be removed by the Govt. They are, thus, independent from the day –to- day control of the Ministry. Independence is very vital for healthy growth and development in Higher Education and this will be lost once the new Bill comes into existence.

Whatever is proposed to be introduced in the Bill can be added to the existing powers of the UGC by amending its statutes.

The disbursement of grants can be made more effective by resorting to new software and by employing IT professionals. The officers that are handling these sacks of files can be shifted to other jobs.

Even though the UGC is acumbersome organization, a lot of positive changes that happened in Higher Education took place because of their effort and innovative ideas. The various Education Commissions instituted under the aegis of the UGC proposed timely changes and those changes were helpful in making the Higher Education in India keep pace with the fast changing trends in the Education sector in the developed nations of the world.

With regard to the preservation of academic standards, the UGC itself can handle the matter by providing necessary funds to colleges and Universities for the development of libraries and laboratories.Common entrance exams for admission to Universities and colleges can preserve the minimum standard at the entrance level.

India’s universities and colleges are forced to take in a certain percentage of students with lower academic standards through the system of reservation. Academic standards of course would be affected as the educational institutions have to take care of low ranking students.

In the world of global ranking, many considerations like the placement of students, the number of students rejected out of the number of applicants, the teacher-student ratio, innovative projects etc are taken into account. India with a lower industrial production cannot offer placements to its students in India itself. Therefore it may not be possible for our institutions to be found among the best universities of the world.

What we can we do is to offer better facilities and qualified teachers in our colleges and universities. Teachers should be available for mentoring, tutoring and research guidance in our campuses. Part-time faculty and moon-lighting should not be allowed.

Hence, we propose that the Government should keep the present structure of the UGC with necessary modifications.

…………………………………..

The Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of UGC Act) Bill 2018:A Rejoinder to the cause celebre (from the Conference of Catholic Colleges of Karnataka (CCCK) and Xavier Board of Higher Education in India)

Subject: Comments, Suggestions and Responses to the Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of UGC)Bill 2018.

The document being presented to you emerges from a detailed discussion on the proposed Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of UGC) Bill2018, which the Ministry of Human Resource Development has proffered to the general public for inviting comments and suggestions, through the Press Release dated 27/06/2018.

The discussion pertaining to the HECI were held under the aegis of the Conference of Catholic Colleges of Karnataka (CCCK) and Xavier Board of Higher Education in India. The CCCK, as a forum, at the state level was born on 25th October 1977 to bring the Catholic institutions of Karnataka under one umbrella to discuss issues that affected the Christian Institutions of Higher Learning in Karnataka, and the Xavier Board is a registered society that is a National Association of all Catholic Colleges in India, encompassing close to 350 Colleges and 6 Universities, across the country.

At the outset, we place before you a concern pertaining to the time allotted, by the MHRD for a comprehensive analysis of the bill, by the general public and institutions of higher learning, have been quite short. The MHRD made public the proposed the HECI Bill on 27th June, 2018 and set thedeadline for 7th July, 2018 to send in the responses. A mere 11 days for discussion, is too short a time to posit any serious and formidable critique to the bill, from various stakeholders such as Teachers, Students and parents, who ultimately would be affected by this legislation. Given that education has its ramifications on the nation and society as a whole; it is of utmost importance, that the MHRD recognize the magnitude of this bill. In the interest of all the stakeholders, and the nation, we request you to extend the deadline for submission of comments and suggestions to a later date.

Having stated this, let us take this opportunity to state on record, that the intention with which the MHRD has introduced the Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of UGC) Bill, 2018wherein you have identified the issues of quality in higher educational institutions of India; which is also affirmed through the QS World University Ranking wherein Indian universities have failed to make a mark, time and again, which is an indicator towards the ills that are confronting universities in our country; is shared by us as well. However, the panacea provided by the MHRD to correct the anomalies of the education through the proposed HECI Bill, 2018 is premature and fraught with problems. We would like to present our arguments, to qualify our statement.

The points presented below reflect our trepidations over the Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of UGC) Bill, 2018:

-

The Bill is ambiguous on several counts. It fails to provide a clear cut section on “definitions” that clarify what the legislation means by “quality”; “less government and more governance”; “affordability” etc.

-

The proposal to dissolve the UGC is premature and replacing it with the HECI provides room for distortions and arbitrariness in promotion of quality education. The UGC as a premier body is a body of intellectuals meant for intellectuals that has been functioning for over 60 years now. Instead of replacing the UGC with HECI, we strongly recommend strengthening the structural and procedural aspects of the UGC.

-

The Bill also introduces the dichotomy between the “quality” control, managed by the HECI; and the grant control, solely the prerogative of the MHRD. The UGC presently performs both these functions, and it has done it with considerable success. We propose that the UGC should continue performing both these functions. Given the role assigned to the HECI and the MHRD, in the HECI Bill, the intention of centralizing the system of funding is clear.

-

The Bill has not been deliberated with stakeholders at the state level. Education as a subject is within the domain of the Concurrent List. Therefore, the Centre and the State have an important say in matters pertaining to education. However, a careful analysis of the bill clearly point towards the exclusion of states in matters of higher education. The bill provides room for the centre to be the sole authority in matters of education.

-

The entire process of quality assessment performed by HECI and the pattern of funding could be fraught with friction and also arbitrariness exercised in extension of grants to institutions.

-

The bill also introduces a system which rules out the face to face interaction between the higher education institution and the funding body.

-

Why the legislative autonomy is centralized it should be more consultative, deliberative and democratic?

Concerns:

8) Ref: Section 3.6: While the UGC Act 1956 clearly mandated that the Chairman of the Commission “shall be chosen from among persons who are not officers of the Government or any State Government” – precisely with a purpose to maintaining the autonomy of the Commission from any form of direct interference by governments – Section 3.6 of the Draft HECI Bill drops this necessary condition for the Chairperson’s appointment. The Chairperson of the proposed Higher Education Commission can now be selected from among functionaries of the Central or State governments, provided he/she satisfies either of two conditions listed under Section 3.6 – none of which comes into conflict with his/her holding an office of the government at the time of appointment.

Not only that, the same Section 3.6 makes the appointment of the Chairperson of HEC incumbent on the decision of a Search-Cum-Selection-Committee (ScSc), headed by Cabinet Secretary and flanked by the Secretary of Higher Education (both GoI employees). The principle of non-intervention that was enshrined in the letter of the UGC Act, as an acknowledgment of the need for autonomy in educational policy-making, is discarded by the proposed HECI Bill with regard to the very setting up of the Commission.

9) Ref: Section 23: The element of criminality and culpability mentioned in the bill is un-constitutional and against natural justice, especially in the context of a proposed educational bill.

-

Ref: Section 15(4)(l): The HECI is empowered to “specify norms and processes for fixing of fee” and to advise governments on “steps to be taken to make education affordable for all”. While the UGC Act had a very detailed section on fees (as well as subsequent regulations) and a prohibition on donations, the HECI Bill makes this singularlyand is the most important provision mere matters of advice. This also signals the move from a state subsidy model to a loan-assistance policy for select private individuals – thus making way for a general user-pay principle in the funding of public education.

-

Ref: Section 24: As per the Sections 12(e)-(g) of UGC Act 1956 prescribes an advisory role for the Commission, with regard to information necessary or sought by the Central or State Governments. The Draft HECI Bill 2018 performs a complete inversion of this. It mandates the setting up of an Advisory Council within the Commission, chaired by the “Union Minister for Human Resources Development” and with “Chairpersons/Vice-Chairpersons of all State Councils for Higher Education as members”. The presence of a government-controlled advisory organ in the Commission, headed by the HRD Minister, puts all pretensions of legislative autonomy to rest and structurally subordinates higher education to the political intentions of the government of the day.

-

Ref: Section 3(6) (b): We find it objectionableof the Draft Bill maintains that the Chairperson of the proposed Higher Education Commission of India may be “an Overseas citizen of India”. We find this unacceptable, as the Chairperson of such a Commission must be someone who is a resident citizen of India, bound by its Constitution, with the requisite experience of teaching/administration in the Indian Higher Education sector.

-

Ref: Section 3(8): Teacher representation is minimal for HECI. The quantum of representation in UGC of teachers is optimal. Reform the UGC and deal with the problem rather than introducing the HECI. Eminent scholars and National Fellows should have a greater representation in the UGC.

-

Ref: Section 15(3)(a): The existing reservation system for the SC/ST/OBC and the linking of quality aspect to the higher educational institution suffer from structural defects. The system would not be geared to take into account the deprivation factor that the community has been confronted with. The HECI Bill does not provide a “weighted formulae” to uniformly assess the issue of quality across social classes. This would be detrimental to the reserved community with reference to learning outcomes specified in 15(3) (a).

-

Ref: Section 15(3)(b): We should follow the UGC prescribed minimum standard for teaching and research as institutions for higher education focusses on epistemic freedoms. Maximality is a relative concept.

Conclusion:

The CCCK and Xavier Board unanimously endorsed that the UGC as an apex body for higher education should continue. We further propose that MHRD should correct the anomalies within the UGC to enhance its functioning. A hurried step towards completely abolishing the UGC and replacing it with the HECI could prove detrimental to the higher education sector, and the purpose with which the Bill is introduced, i.e. to improve the quality of education in the country would stand defeated.

…………………..

Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of University Grants Commission Act) Act 2018: (Recommendations to MHRD – from Loyola College Chennai)

Based on the deliberations held at Loyola College with 350 academic staff, a review was conducted on the proposed draft of the Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of University Grants Commission Act) Act 2018 and its advantages and disadvantages were discussed. At the outset the draft presents a framework of the Higher Education Commission of India, its content reveals many ambiguities in the structure that gives room for taking forward a political agenda rather than improving the quality of higher education.

The following recommendations evolved out of the deliberations:

1.Since an effort is being taken to revise the higher education agenda of the nation, a down time of ten days for discussion and deliberation is highly inadequate. Hence, it is recommended that more time be given to organize discussions among stakeholders of higher education to come up with concrete deliberations.

2. In an attempt to replace the UGC with HECI, the draft does not present a clear vision and mandate for this body. This leaves room for much ambiguity. Hence, there is a need to envisage a clear pan-Indian vision to cater to the needs of the burgeoning India.

3. In the name of deregulation, there seems to be an attempt to bring in a far more bureaucratic structure with an emboldened regulatory mechanism which will hinder the advancement of higher education in India.

4. The expansion of the structure that gives a very little scope for people with academic excellence is seen as a dangerous move to cauterize higher education and stunt higher education. We recommend that the larger part of the administrative structure should include educationists who have a proven track record of academic excellence.

5. The draft tends to micro-manage the institutions which will impinge upon the rights of the most deserving disadvantage and discriminated sections of society. Therefore we recommend that a broader inclusive approach should be maintained while drafting the higher education policy in pursuit of excellence.

6. The draft is devoid of mentioning anything about the allocation and distribution of funds. It is recommended that a robust mechanism is setup with clear guidelines of allocation and channels of distribution of funds.

7. It is found that the HECI would play not only an implementing role but also a policing role for higher education. This could result in punitive engagement of the institution based on subjective experiences. We recommend that the body empowers itself with monitoring and evaluating mechanisms that are objective and time tested.

8. The draft clearly paves way for disinvestment from higher education and encouragement of foreign direct investment and privatization of higher education. This will not only prevent the access to higher education but also dissuade the disadvantaged sections from accessing quality affordable higher education that has remained as a window of opportunity to alleviate poverty along with other social maladies. Therefore, it is recommended that more investment avenues are to be opened by the government to create an empowered India. There needs to be an assurance of a minimum of 6% of GDP to be allocated for educational purposes.

9. The current draft of the HECI does not deal with the challenges faced under the UGC act. The amendments to the UGC act can very well deal with the issues and concerns of inadequacies arising thereof. We strongly feel that the new proposed draft is a change for the sake of change rather than addressing the problems that are currently being confronted.

10. The present HECI act unilaterally legislates on a concurrent subject thereby encroaching on the rights of the state government and jeopardizing constitutional federalism.

11. In the present HECI act, the exclusive focus and privileging of learning outcome is a short-hand favouring commoditization of the education system.

12. It is recommended to decentralize the higher education system appropriately with greater autonomy and powers to State and Institutions of higher education with the provisions of assurance and safe guarding minority rights.

13. It is recommended to revisit the relevance of unified standardization, excellence and the outcomes for various systems in accordance with the diverse nature of our nation.

14. It is recommended to revisit the penal powers mentioned in the draft of the commission.

15. The various provisions of the HECI act overrides the provisions of the pre-existing acts associated with setting academic standards which need to be viewed retrospectively.

……………………………………………..

Comments on the Draft Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of University Grants Commission Act) Act 2018.( from SPCSS-TN : Mr. P.B. Prince Gajendra Babu)

The Time given for sending response is too short and the Draft Act is Not available in any of the Indian Languages

1. The Draft Act was placed in public domain on 28th June, 2018 and Comments

were asked to be submitted before 7th July, 2018.

2. The time given for sending comments is too short, hardly 10 days, to study and respond on the Draft Act that will have far reaching effect on the higher

education field.

3. The Draft Act is available only in English and it is not available in any Indian language. It will not be possible for people whose mother tongue is Bengali,

Gujarati,Marathi, Tamil, Telugu and other Indian languages to study the Draft Act and comment. The implications are far reaching and how can one be expected to comment without understanding the issue thoroughly. This is against Article 14 of the Constitution of India.

There should be wider consultation and public hearing on such vital issue:

4. The University Grants Commission (UGC) was established on the Recommendations submitted in 1949 by Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan Commission. The UGC Act, 1956 made UGC a statutory body.

5. The Recommendations of the Dr.Radhakrishnan Commission are relevant even

to the present day and the role of UGC is unique and it needs to be strengthened and not weakened or replaced.

6. The proposal to replace UGC will have far reaching consequence. It may even

destroy all Public Funded Institutions, built over years, through hard labour of

eminent educationists and with tax payers’ money. The Indian working class has

contributed to the State funded Higher Education Institutions through their savings in LIC and Provident fund.

7. If the standards are set in accordance to the market needs without taking into

account the societal needs, the human development and social progress cannot be achieved. A proposal that will have such a far reaching consequence needs a wider consultation and public hearing in every State and Union territory.

The Draft Act,prima facie, is in gross violation of Article 246 of the Constitutionof India. It alters the basic structure of the Constitution of India:

8. The Entry 44 of List 1– Union List in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution

of India reads as follows “Incorporation, regulation and winding up of corporations, whether trading or not, with objects not confined to one State,

but not including universities.”

9. The Entry 32 of List 2 – State List in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution

of India reads as follows “Incorporation, regulation and winding up of corporation, other than those specified in List I, and universities; unincorporated trading, literacy, scientific, religious and other societies and associations; co-operative societies.”

10. Section 1 (2) of the Draft Act reads as follows “This Act is applicable for all higher educational institutions established, under any Act of the Parliament excluding Institutions of National Importance so notified by the Government,

Act of State Legislature and to all Institutions Deemed to be Universities so notified by the Government.”

11. Section 15 (3) (g) of the Draft Act reads as follows “Order closure of institutions which fail to adhere to minimum standards without affecting the student’s interest or fail to get accreditation within the specified period;”

12. According to the Article 246 Read with Entry 32 of List 2 and Entry 44 of List 1

in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution of India, Incorporation,

Regulation and Winding up of a University is an exclusive domain of the State

Government and only the State Legislature can make Laws on this subject

and the Union Government cannot bring in a legislation with provisions either to regulate or close University that is established by the State Government under the State Legislation.

13. The effect of the Draft Act would be that all the enactments made by all the

States in India establishing various Universities till date would become

obliterated. Therefore the Draft Act is directly in conflict with the Principle

of Federalism enunciated by the Constitution and approved by the Supreme

Court of India in various judgments.

14. The largest constituted Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court, in its judgment in 1973 in the Keshavananda Bharati Case has declared that the Federal Character of the Constitution as the Basic Structure which cannot be altered.

15. The Draft Act is a deliberate attempt to alter the Basic Structure of the

Constitution of India. The Draft Act encroaches upon the Rights of the State Government to incorporate, regulate and wind up a University.

16. Section 19 & 20 of the Draft Act makes it mandatory for a University

established by the State Legislature to get authorization from the Higher

Education Commission and such authorization shall be revoked by the Higher Education Commission, if the Commission is satisfied that a University is not in a position to maintain the standards prescribed. This is a blatant violation of the Right of State Government and it is against the Spirit of the Constitution.

Education is Part of Culture. In a land of CulturalDiversity, uniformity cannot be a desired goal:

17. India is a country that has vast diversity in Landform and Climate, which influence the culture of the people. Education is part of culture and there can be no uniformity in any kind of educational activity, including the learning out come. India is described as Mosaic of Culture. Such diversity should be celebrated and should not be allowed to be destroyed with structural homogeneity.

18. Section 3 Sub-Section (6)(b) of the Draft Act makes provision for appointment

of an Overseas Citizen of India to the post of the Chairperson of the Higher Education Commission. An overseas citizen of India is literally a foreign national. The person is born and is living in a foreign land. The Person’s ancestors were Indians. Such persons will not have direct exposure to the social & cultural issues of the Indian Society at present. A university is part of the community, hence, a Commission that is to regulate Universities cannot be headed by a Foreign national, who is born, brought-up and living in a foreign land. The freedom fighters who gave up even their lives for the freedom of this nation would not have dreamt that after seventy years of

Independence, there will be dearth for educationist in India and this nation

will be searching for suitable hand from among the citizen of another nation. The Draft Act fails to recognize the cultural components of education.

19. The Draft Act does not recognize the diversity. The Draft Act treats education as a commodity and looks at Universities as factories that is supposed to bring out products to meet the market needs.

The Draft Act will widen the disparity and is against the interest of the socially and Educationally Backward Class:

20. Regional imbalances are still to be addressed. People living in Khasi, Garo

hills, desert of Rajasthan and in remote areas of various States still do not have equal access even to Primary Education. The Social disparity and

economic inequality has not reduced to desired level. The Recommendation

made by Kothari Commission for establishing Common School System and

developing all Indian Languages is still a dream.

21. Under these circumstances affirmative action, as guaranteed by

Constitution of India for Educationally and Socially Backward Classes can be best achieved only when the grant and inspection remain with

an independent statutory body and that is the mandate for UGC.

22. If a body that regulates Higher Education Institutions is relieved of both the functions of providing grant and inspecting the Higher Education Institutes,

then the vision, as stated in the Preamble of the Constitution of India, cannot be realized.

23. Education has historically meant a socio-cultural process that unfolds the

creative and human potential of children and youth in the larger and

collective interest of the society and, instead of maintaining status quo, plays

a socially reconstructive and transformative role to fulfil civilisational

aspirations for Republicanism, Liberty, Equality, Justice, Human Dignity,

Plurality, Social Harmony and Universal Peace.

24. The Draft Act on the contrary speaks of ‘Merit alone’- even without defining what is merit- concept that is based on market needs and such approach will not lead to the emancipation of socially and educationally backward classes.

Such ‘market need target’ concept will only help the upper strata of society

to completely occupy the Higher Education field, which was the case before

the Commencement of Constitution of India. The Draft Act will take us to the

Pre-Independence Era. Draft Act will only help to widen the disparity.

The Draft Act is a Road Map for Bringing Education under WTO Regime:

25. Reading the contents of the General Agreement on Trade in Service under

World Trade Organization (WTO) and the contents of the Draft Act, an

apprehension is cast, whether the Draft Act is to facilitate provision for market access in education under WTO –GATS regime.

26. The Draft Act does not distinguish between a State University and Private

University. This is precisely what the WTO- GATS mandates. WTO-GATS demands a level playing field and the Draft Act makes it possible. The Draft

Act is not in accordance with the Constitution of India but in accordance with

wishes of the WTO.

27. The government of India must come out openly on the progress of negotiation

in WTO, particularly in the field of education. If it is not to satisfy anybody,

then, such haste is not required to dismantle the sixty year old statutory body

that is mandated to ensure sufficient grant is provided to all Government and Government aided institutes, so as to ensure that education remains a social good.

28. A ‘Bill’ before it is placed in the Parliament is termed as a ‘Draft Bill’. A ‘Bill’

becomes an ‘Act’ only after it secures the assent of the President. Surprisingly

this document is termed as Draft ‘Act’. Further, Section 19 Sub-Section (1) of

the Draft Act mentions about Sub-Section (7) of Section 20. But Section 20 has

only 5 Sub-Sections. This is a sample to prove thehaste with which the whole

issue is handled.

Appeal for Withdrawal of the Draft Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal University Grants Commission Act) Act 2018 and to Strengthen UGC:

29. For the reasons stated above, we humbly request the Government of India to

withdraw the Draft Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal University

Grants Commission Act) Act 2018and take effective measures to strengthen the UGC to realize the vision as stated in the Preamble of the Constitution of

India.

………………………………………………

RESPONSE TO THE DRAFT “HIGHER EDUCATION COMMISSION OF INDIA” (HECI)- from the Telugu Catholic Bishops’ Council:

From the time of Indian independence, till date, Higher Education has been entrusted in the hands of University Grants Commission, which executes its function in an extraordinary way, giving quality education and maintaining standards. We can say it as “Pride of India” by its products. UGC of India from the time of its establishment has created eminent Doctors, Scientists, Scholars, Technicians, Politicians and many who are working not only in India but also in many other countries throughout the world. It also established many Regional Centres for vigilance and observation of its Institutions and their standards.

It is our opinion that there is no immediate necessity to repeal UGC, as none of its activities or functioning is harmful for the growth of India or damaging the Democratic character of India. Secondly the functioning of the HECI is also the same as that of UGC. Moreover the Scientists who are doing research in the various fields will get discouraged with the repeal of UGC.

When the Functionary or the Executive Committee is more or less similar to that of the UGC, we can’t find much difference, but for the change of name. In such case why to repeal an ancient body like the UGC? However the list of functions of HECI are already found in force by many existing Universities as I have noticed in Hyderabad and in Warangal. Further it will be very easy for any individual institution to have access to Statutory Bodies / Bureau like PCI, AICTE, NCTE etc., instead of one common or combined HECI.

One thing is that I am unable to understand s to what mistake UGC has made for its repeal. If the Government wants to make certain reforms or change, the same can be implemented through AICTE, NCTE or through the University Grants Commission. Hence in conclusion, we do not encourage the dissolving / repealing of such a prestigious bureau like the UGC with HECI.

(from Archbishop Thumma Bala of Hyderabad)

RESPONSE TO THE DRAFT “HIGHER EDUCATION COMMISSION OF INDIA” (HECI) – (from Suhasini and Other Individual Colleges)

In response to the public notice issued by the Ministry of Human Resource Development seeking feedback on the Draft Higher Education Commission of India Bill 2018 from “educationists, stakeholders and general public”, I would like to strongly oppose this move to centralise, bureaucratise, and establish absolute government control on higher education.

In its Press Release, the government has cited the bill as “downsizing the scope of the Regulator”, “removing interference in the management issues of the educational institutions”, and improving academic standards, but a reading of the Bill, actually reveals the opposite intention, that will have a disastrous effect on the access that India’s young people will have to higher education, as well as the creation of jobs in the education-sector.

By withdrawing financial powers from the regulator and handing them over to the central government, and by giving the HECI unilateral and absolute powers to authorise, monitor, shut down, and recommend disinvestment from Higher Educational Institutions (henceforth HEIs), the Draft Bill will expose higher education in the country to ideological manipulation, loss of much needed diversity as well as academic standards, fee hikes, and profiteering. It will also contribute to greater marginalisation and disadvantage of millions of students, particularly from the socially oppressed sections, and imperil many educational institutions. In my opinion, rather than dismantling the University Grants Commission, the attempt must be to strengthen its consultative and enabling architecture, in such a way that promotes access, diversity, quality.

I would like to place on record my objections to the clauses to the Draft HECI Bill, as below. I urge the government to withdraw this Bill, and initiate a discussion with teachers and students organisations and other stakeholders for suggestions as to how the UGC and its functioning may be improved. Involve more the real stakeholders.

Section 3.6: While the UGC Act 1956 clearly mandated that the Chairman of the Commission “shall be chosen from among persons who are not officers of the Government or any State Government” – precisely with a purpose to maintaining the autonomy of the Commission from any form of direct interference by governments – Section 3.6 of the Draft HECI Bill drops this necessary condition for the Chairperson’s appointment. The Chairperson of the proposed Higher Education Commission can now be selected from among functionaries of the Central or State governments, provided he/she satisfies either of two conditions listed under Section 3.6 – none of which comes into conflict with his/her holding an office of the government at the time of appointment.

Not only that, the same Section 3.6 makes the appointment of the Chairperson of HEC incumbent on the decision of a Search-Cum-Selection-Committee (ScSc), headed by Cabinet Secretary and flanked by the Secretary of Higher Education (both GoI employees). The principle of non-intervention that was enshrined in the letter of the UGC Act, as an acknowledgment of the need for autonomy in educational policy-making, is discarded by the proposed HECI Bill with regard to the very setting up of the Commission.

Section 3.6(b) of the Draft Bill maintains that the Chairperson of the proposed Higher Education Commission of India may be “an Overseas citizen of India”. I find this unacceptable, as the Chairperson of such a Commission must be someone who is a resident citizen of India, bound by its Constitution, with the requisite experience of teaching and administration in each and every Indian Higher Education sector.

Section 3.8: It is apparent from Section 3 of the Draft Bill that teachers have been pushed out of the Commission, almost entirely. Though the total number of members of the Commission has gone up from ten to twelve, the representation of teachers has been ominously reduced to just two. Whereas the earlier UGC Act ensured a minimum of four teachers in the 10-member Council and that at least 6 were not officers of State/Central governments (Section 5.3, UGC Act 1956), the HECI is proposed to be packed with government nominees, chairpersons of regulatory bodies, university administrators, but no teachers. In a body that is purportedly responsible for determining quality of education, learning outcomes, and other functions of academic content, we find it shocking that university professors — the only group qualified to deliver in this respect — have been so purposely reduced to an ineffectual minority. The UGC Act provision that not less than one-half of the members of the commission must not be officers of the Central Government or of any State Government has been omitted, leaving the door open for a commission comprising an overwhelming majority of government officers. Further, inclusion of a “doyen of industry”, where there are no definitions of who so qualifies to be termed as such, is highly inadvisable and risky as we can understand.

Sections 8 and 9: The Draft HECI Bill provides for Chairpersons and Members to declare the extent of their interest, “whether direct or indirect and whether pecuniary or otherwise, in any institution of research or higher educational institution or in any other professional or financial activity.” (Section 9.1) We find that the measures to address conflict of interest in the Draft Bill to be highly inadequate — mere publicity on the HECI website and self-recusal from participation in relevant decisions can be no deterrent to attempts to mould and formulate the national educational policy for self-interest.

Section 12.1: The Bill provides for appointment of the Secretary to the Commission, “who shall be an officer in the rank of Joint Secretary and above to the Government of India”. Since as Section 14 goes on to state, all “instruments” – barring “orders and decisions of the Commission” – shall be “authenticated by the signature of the Secretary or any other officer of the Commission authorised in like manner”, it is amply clear that all policy-correspondence as well as issues of funding will be incumbent on the pleasures of the government. This corrodes the very ground of legislative autonomy that justified the very existence and functioning of the University Grants Commission.

Section 15: Although the HECI Act is being touted as a means of ensuring both quality of education as well as greater autonomy to universities, Section 15.3 of the Draft Bill empowers the HECI to lead to a further degradation of both.

15.3(a): The HECI is empowered to specify “learning outcomes”, which invokes formulaic expectations of what university education must be oriented towards. Even the UGC’s efforts towards framing model syllabi as guides for all colleges/universities across the country – under the guise of a Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) – have been severally pointed out as inadequate, given the disparate conditions and infrastructures of learning in widely divergent local contexts. To say that students must learn X and Y by the first year, for example, is to void the classroom situation of material references to or historical indices of privilege and discrimination. To argue that SC/ST/OBC students, with their histories of deprivation, must achieve the same “learning outcomes” as those coming from metropolitan contexts of privilege is to argue against the very logic of reservation in public institutions. This will eventually push the frontiers of higher education towards a standard quantum of ‘merit’ (measured as learning outcome), thus forcing those who cannot live up to it to either drop out of universities or fail miserably. While very general directions as what should be the curricular design of what, say, an undergraduate programme should guarantee its learners are desirable, any measure that stamps out diversity as well as innovation and original educational initiatives is unwelcome.

15.3(b): The HECI is also empowered, like the UGC was, to “lay down standards of teaching / assessment / research”. It should be noted that the UGC could, correctly, only set minimum standards, so the proposed HECI has been given extraordinary powers of undermining institutional autonomy. The substantive struggle of universities with the UGC has been in the last few years, to ensure that its minimum regulations do not achieve the status of maximality. It is imperative to maintain institutional autonomy if quality is to be ensured, and an enabling framework that allows universities to harmonise their standards with the regulator’s expectations must be created.

15.3(c): The HECI has been given the power to carry out a yearly academic performance evaluation of universities. We find this bureaucratisation unacceptable and completely unfeasible. To audit the performance of public institutions and ascertain their fitness to function is to also come up with differential funding parameters for different orders of ‘performance’. This kind of graded financial liability (on the part of the government) towards grossly disparate contexts of performance across HEIs will not only create a few centres for excellence at the cost of all others, but will also strengthen existing hierarchies between regional and metropolitan institutions. Further, it is highly unlikely that the Commission will be able to do any kind of meaningful yearly evaluation of the 789 universities that the UGC website says are in existence today. All that will result from this power is a highly partial process that will disrupt the functioning of universities, and convert ‘performance’ into a punitive category.

15.3(d): The Draft Bill makes the HECI inherit the UGC’s function of promoting research, except that the divestment of its financial powers means that it will only be able to “coordinate with Government for provision of adequate funding for research”: This will make all HEIs subject to the interests of the political parties in power, and subject directly to their ideological manipulation. Compared to the UGC, which had financial powers, and because it was composed of academics and was tasked with making decisions after consultation with universities, this will make funding for research contingent on political considerations rather than those attendant on international standards of knowledge creation. This will have an adverse effect on the standards of research carried out in Indian universities. Furthermore, it also appears that the HECI will no longer have funds of its own to promote research like the UGC did, so that the Commission’s role in furthering research (through fellowships, research projects, travel grants) will be non-existent.

15.3(e): The HECI is supposed to evolve a robust accreditation system for evaluation of academic outcomes by various HEIs, thereby subsuming the role of the National Accreditation and Assessment Council. This proposal is to tie in NAAC scores to funding allocation, at the very least (as well as performance targets), in a manner that will only prove detrimental to the development of teaching and research in newer and less privileged institutions. One presumes that the metric that will be employed is that the lower the NAAC grade, the lower the government funding and the more impossible the improvement. Such policy direction has already been hinted at in the recommendations of the Subramanian Committee Report for New Education Policy 2016. This will only institute a terrible vicious cycle, which makes performance the policy-basis for funding – rather than the other way round.

15.3(g) and 15.4.(f): The HECI is empowered to “order closure of institutions which fail to adhere to minimum standards without affecting the student’s interest or fail to get accreditation within the specified period”. This power to close down institutions in a country that fails to provide enough HEIs has to be wielded with great caution, and with checks and balances, and a clear and detailed specification of what protecting the student’s interest must entail. While there is no question of granting impunity to incidents of fraud being perpetrated on students and their families — and it should be noted that this is a penal offence which can easily be prosecuted — the non-availability of enough publicly funded HEIs is the major reason why students flock to such institutions at exorbitant costs. Arbitrary closure, or threats thereof, shall not only deprive students of the only education that they can access, it will also put the livelihood of teachers and staff employed in these institutions in peril. Finally, such unbridled power shall in all likelihood fuel corruption.

15.4(c) and 15.4(d): The HECI is empowered to specify standards for grant of autonomy and Graded Autonomy. The proposed move, which has in fact already been initiated by the UGC, is intended to divest the state’s investment in HEIs that perform according to standards it sets. This will entail a marketisation of HEIs, fuelling fee hikes and greater job insecurity, and will invariably lead to a complete constriction of access to the better performing institutions to poor and disadvantaged students (who constitute the bulk of the population entering higher education).

15.4(g): The HECI is also tasked with the development of “norms and mechanisms to measure the effectiveness of programmes and employability of the graduates”. The criteria used to determine “employability” do not come from within the educational domain, as the availability of employment in the country has to do with macro-economic factors. To transfer the burden of employability onto the HEIs, in the form of a conditionality for funding or as a performance index, is unfair.

15.4(l): The HECI is empowered to “specify norms and processes for fixing of fee” and to advise governments on “steps to be taken to make education affordable for all”. While The UGC Act had a very detailed section on fees (as well as subsequent regulations) on fees and a prohibition on donations, the HECI Bill makes this singularly most important provision mere matters of advice. This also signals the move from a state subsidy model to a loan-assistance policy for select private individuals – thus making way for a general user-pay principle in the funding of public education.

15.7: The HECI shall also “discharge such other functions in relation to the promotion, coordination and maintenance of standards in higher education and research as the Central Government may subject to the provisions of this Act, prescribe.” With the HECI’s forfeiture of minimum structural autonomy from the government of the day, it is now perfectly possible for the latter to dictate the terms and conditions of enrolment as well as content of academic courses in the name of ensuring uniformity.

Although the HECI Act is being publicised as giving autonomy to HEIs, the provisions of the Draft Bill actually invest the HECI and the Central Government with extraordinary powers, without any checks and balances. Individual HEIs have no power to demand consultation, inquiry, or even appeal against any of its decisions. The HECI Act sets up the regulator as a gatekeeper who manages the market and the tractability of the workforce it produces — the goal is to create an authority that has total control over the market, including the power to expel those that exact continued subsidy from the state. Compliance will demand from HEIs absolute obedience, to an authority that is ruled by political expediency and with very little expertise in education.

Section 16.1: By this provision, no HEI established after this Bill is passed can start awarding degrees unless it is authorised, and Universities established before it will be considered authorised for THREE YEARS only, after which it may be revoked. This will create grave uncertainty in well-established institutions, and will certainly harm students’ interests, who may be enrolled in courses for longer than three year duration. As the section makes authorisation contingent on achieving a set of goals over a decade, this will lead to re-orientations in HEI policies based not on academic considerations, but severe pressure on administrators and teaching communities. The provision for imposition of penalties contained in Section 23 may be useful for a political party wishing to enforce instant obedience, but are of no value to those actually working in the education sector, where a culture of reasoned argument and careful consideration must be the norm.

Section 24: Sections 12(e)-(g) of the UGC Act 1956 prescribed an advisory role for the Commission, with regard to information necessary or sought by the Central or State Governments. The Draft HECI Bill 2018 performs a complete inversion of this. It mandates the setting up of an Advisory Council within the Commission, chaired by the “Union Minister for Human Resources Development” and with “Chairpersons/Vice-Chairpersons of all State Councils for Higher Education as members”. (Section 24.1) The presence of a government-controlled advisory organ in the Commission, headed by the HRD Minister, puts all pretensions of legislative autonomy to rest and structurally subordinates higher education to the political intentions of the government of the day.

Section 26: The provision that the HECI Act will have an overriding effect is extremely disturbing, as this will effectively nullify the various Acts of Parliament that have constituted existing universities. These acts have promoted a diversity of orientation in institutions, suited to the plural needs of our diverse country, and have maintained the distinctiveness and relevance of our institutions to their local and national milieu. Reducing all HEIs to a dull uniformity will not produce a responsive higher education. Since HECI’s “Regulations relating to promoting quality and setting standards shall have prior approval of Central Government” (Section 29), it is the government who will effectively run every single HEI in the country.

The Draft HECI Bill will entrench a regulatory system that will just liquidate otherwise all the investments in education that the Indian people have made through the taxes they have paid for the last seven decades. The “changing priorities of higher education” – as the Draft Bill 2018 claims to address – do not warrant the setting up of a Commission that delinks regulatory functions from funding commitments. By desiccating the UGC’s grant-disbursal powers and locating them solely in the Central government, the proposed Commission will become a means to ensuring ideological compliance from universities as the pre-condition for public funding. This further produces the risk of a punitive disciplining of institutions, through a deliberate withdrawal of funds by the government at will, on the slightest pretext. Most significantly, not only does the Draft HECI Bill violate the very idea of autonomy that the UGC was modelled on, but it also goes a long way in insisting that universities and other higher education institutions be reduced to organs of the government.

I believe that the HECI Act 2018 has the potential for adversely affecting the future of all HEIs in the country by destroying the ground for their autonomous functioning and mandating a compulsory interference from governments. It would be best therefore to withdraw this proposed Act, in the independent interests of a “scientific temper” and “spirit of inquiry” that the Indian Constitution enjoins us to.

Other Responses from individual Colleges:

-

3 (8) f): One doyen of Industry: I do not understand why a doyen is included in the list of members of the proposed HECI.

-

15 (4) l): Specify norms and processes for fixing of the fee chargeable by Higher Educational Institutions and advise Central Government or State Governments as the case may be , on steps to be taken for making education affordable for all:

This may bring about unnecessary Government interference in the management of Private State Universities/Institutions and make it difficult for them to impart quality education without the necessary financial support.

-

25. Policy relating to national purposes as may be given to it by the Central Government: This would make it very easy for any Government or Political Party in power to dictate its interests to the Universities/Institutions of Higher Education.